Chaos in container shipping!

Container shipping costs have jumped drastically along some routes as the coronavirus pandemic remaps traditional trading patterns and issues at European ports. Add the delays in the region and you’ll understand our worries. Read the highlights of the market impact, disruption, congestion and container shipping alliances in article by Tom Brown of ICIS.

The recovery of multiple key Asian markets from the pandemic, relative to the ongoing struggles faced in the west, has led to a surge in exports from the region to the rest of the world, with less product going back the other way.

The shift in demand patterns has led to containers returning empty to Asia as demand for exports from the region significantly outstripped demand for imports, increasing costs and lead times for orders.

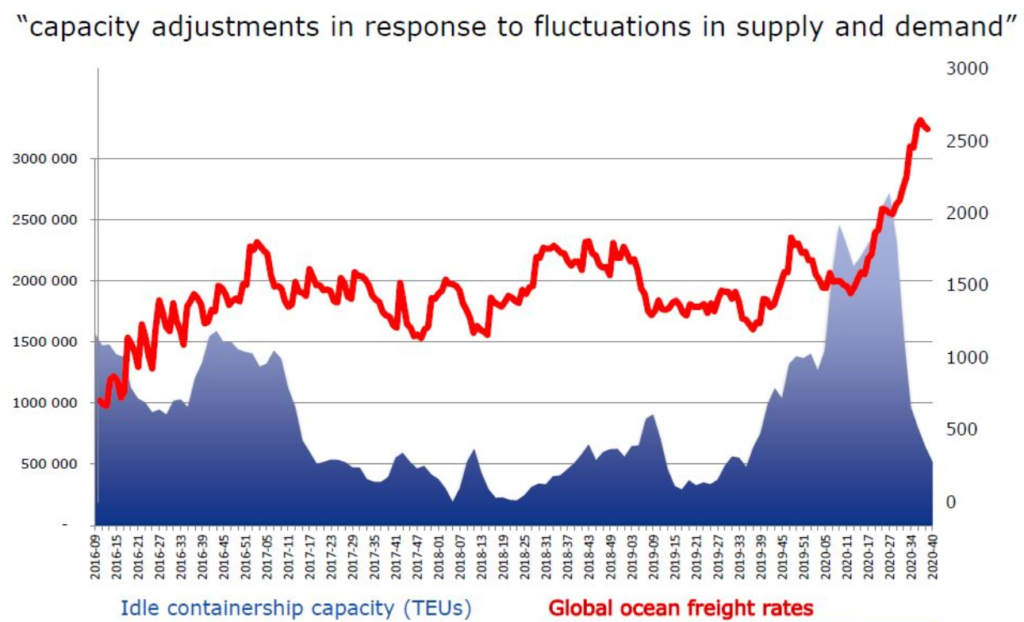

Shipping lines cut capacity drastically during the first wave of pandemic-related lockdowns, and have failed to boost it sufficiently as demand bounced back.

Container availability has been disrupted by too many full containers being stuck in distribution chains west of Suez or in congested ports of entry, with logistics slowed down because of manpower shortages related to coronavirus lockdowns.

MARKET IMPACT

Normally freight costs are around $1,500 for a 20ft container. Now you talk about $5,000. It changes every week! The extent of demand has led to shortages in Asia, with shipping firms going so far as to send additional empty containers to the region just to alleviate some of the pressure.

Sources spoke of shipping freight rates for dry cargo rising three- or four-fold, and lead times dragging from six weeks to eight, at a point where demand patterns are extremely difficult to determine due to the trading volatility seen in the market outlook.

Lockdown measures in many European countries are creating additional headaches for the shipping sector, Some sources report the use of smaller vessels to cut down on mooring fees but resulting in reduced vessel space, and shipper terms changing fast.

All the Asian countries are producing and exporting and not importing, because of Covid etcetera.

Shipping lines are saying they can’t respect their contracts. They say: pay or we won’t ship!

DISRUPTION TO PERSIST INTO 2021

Some Asia sources have expressed expectations that freight container tightness in the region is likely to persist until February 2021.

The Chinese say it will last until March or April 2021, then the cycle of containers should go back to normal.

PORT CONGESTION

Trade disruptions, bulk orders of medical equipment by governments and geopolitical issues such as the UK’s imminent expected departure from the EU customs union, is also causing congestion at ports and storage issues.

Other key European ports have also had issues, with Rotterdam suffering from delays to arrivals and discharges of shipments due to issues with a new IT system.

The practicalities of operating during the pandemic are also exacerbating delays at European ports, with additional health and safety checks, furloughing, and social distancing also slowing the speed that product moves through the ports.

Lockdowns are expected to ease in most European countries but, with the virus still circulating at high rates and restrictions expected to be temporarily eased for a spell over the Christmas break, controls on contact and the potential for staff shortages from illness remain high.

The issues mean that, while supply chains are largely continuing to hold and orders continue to be met, logistics issues are likely to continue exacerbating demand opacity, economic volatility and shifts among buyers to more hand to mouth purchasing habits, making for a treacherous landscape for firms through to the new year.

CONTAINER SHIPPING ALLIANCES

Although shipping cartels were outlawed in 2004, shippers are permitted to operate in alliances to optimize use of shipping space.

The OECD’s International Transport Forum claims that links between these consortia mean a large majority of trade routes to and from Europe are operated by one conglomeration of these groups.

It is concerned that too much information may be shared on volumes, costs and pricing.

The container sector is a lot less fragmented compared to a few years ago. Now the top five owners are controlling close to 65% of capacity.